A Stranger in a Strange Land: Data Science Onboarding In Practice

Andrew Bolster

Senior R&D Manager (Data Science) at Black Duck Software and Treasurer @ Bsides Belfast and NI OpenGovernment Network

This talk was originally prepared for the 2020 Northern Ireland Developers Conference, held in lockdown and pre-recorded in the McKee Room in Farset Labs

Intro

Data Science is the current hotness.

While those of us in these virtual rooms may make fun of the likes of Dominic Cummings for extolling a ‘Data Driven Approach’ to policy, the reality is that Data Science as a buzzword bingo term has survived and indeed thrived in a climate where ‘Artificial Intelligence’ is increasingly derided as being something that’s written more in PowerPoint than Python, ‘Machine Learning’ still gives people images of liquid metal exoskeletons crushing powdery puny human skulls, and those in management with long memories remember what kind of mess “Quantitative Analysis” got us into not too long ago…

Way back in 2012, the Harvard Business Review described Data Science as “The Sexiest Job of the 21st Century”, and since then has been appearing in job specs and linkedin posts and research funding applications and business startup prospecta more than ever.

You’re not really doing tech unless you’ve got a few pet Data Scientists under your wing.

Like some kind of mythical creature, these Data Scientists sit somewhere between Wizards, Artificers, and Necromancers, breathing business intelligence into glass and copper to give the appearance of wisdom from a veritable onslaught of data, wielding swords of statistical T-tests, shields made of the Areas Under Curves, and casting magicks of Recurrent Neural Networks.

Like if Tony Stark and Steven Strange fell into a blender and the Iron Mage appeared, extracting wisdom from the seen and unseen worlds around them and projecting wisdom into the future….

But more often, it’s much more mundane…

However, for an organisation attempting to leverage these mythical Data Scientists, how do you introduce, accommodate, and indeed, welcome these new skills into your production data workflows?

What’s this about?

In this talk we’ll walk through some of the philosophies I’ve arrived at as someone who started off as a lone-Data Scientist now transitioning to team leadership, and what tools I recommend to new hires (and intrigued colleagues) to understand complex production architectures. So, generally, what I wish I knew when I started with modern-ish Data Science workflow.

Also, a couple of dodgy stories from over the years of ‘Data Science Gone Wrong’, that will probably get some questions asked, and hopefully not of me.

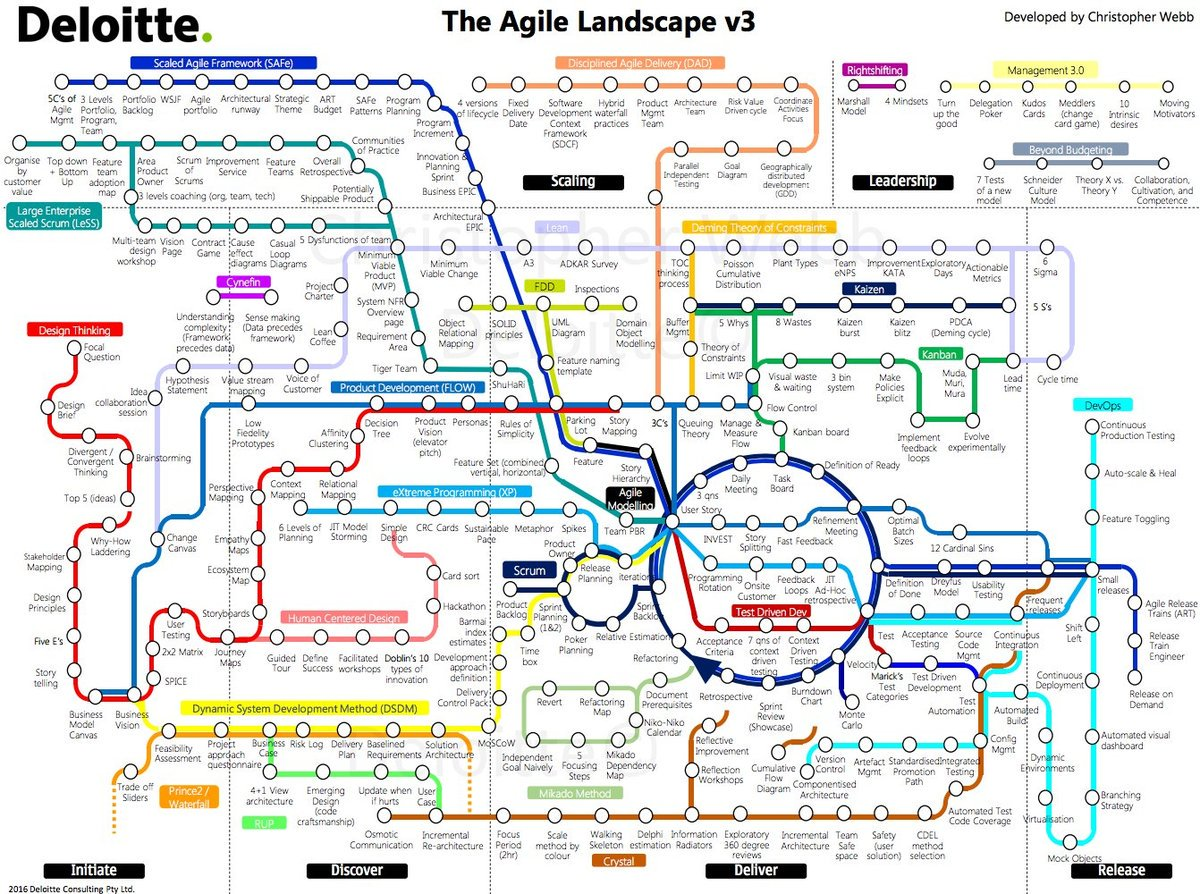

This isn’t going to be a technical Data Science talk, we’re not opening up Jupyter or firing up Spark or Tensorflow or whatever. We’re not even going to talk about Perceptrons or Hidden neurons or homomorphic cryptography. This is about people, processes, how to establish a healthy data science culture.

Anyway, who am I to talk about this stuff?

Who am I ? (AKA you can skip this bit)

My professional background started off by getting robotic dogs to piss on headmasters in front of 200 primary school kids and taking things apart and always having a few screws left over (or loose) at the end.

I eventually turned that “skillset” into something of a trade, by studying electronics and software engineering at Queens.

As part of this I got to test the launch of 4G networks in China from the grey comfort of an office in Athlone, I moonlit as a technology consultant for a marketing and advertising firm in Belfast, used massive clusters of GPUs to optimise cable internet delivery, and spent a summer developing BIOSs for embedded computers in Switzerland.

After that, and just in time for the financial crisis to make everyone question their career choices, I continued down the academic culvert to do a PhD, stealing shamelessly from the sociologists to make their “science” vaguely useful by teaching autonomous military submarines how to trust each-other.

More recently, I worked with a bunch of psychologists and marketers to teach machines how to understand human emotions using biometrics and wearable tech as the only Data Scientist.

This being a small start-up, that meant I did anything that involved Data, so from storage and network administration to statistical analysis, real-time cloud architecture to academic writing, and everything in between. This also somehow involved throwing people down mountains and developing lie detecting underwear. Ahh the joys of Start Ups.

After that I got to be a grown up Data Scientist working in at a cybersecurity firm specialising in real time network intrusion systems, playing with terabytes of historical and real time data trying to read the minds of hackers and script kiddies across the world who are throwing everything they can at some of the internet’s biggest institutions. This was my first taste of being a Data Scientist who wasn’t working completely alone…

What about now? (AKA ‘Start reading here’)

After two years in that I got pinched to build a new team within an established Cyber Security group called WhiteHat Security, that had recently been acquired by NTT Security;

We have 15 years of human expert trained data on if and how customer websites can be vulnerable to attack. We have teams of people working 24/7 to try and break peoples websites before ‘the bad guys’ do to prove that they’re vulnerable, and one way or another, we have those footprints of investigation, and the company wanted to start doing something with that data, so they needed a Data Science team.

I’ve been there a year and this isn’t officially a sponsored talk so I won’t rant, but all I’ll say is I’m still really enjoying the work. Anyway, with all that in mind, I want to look at this ‘How do you spin-up Data Science’ from three perspectives.

- Things that made previous “Data Science” roles suck

- Methods and approaches that I as an Individual contributor came to use to make my own life easier

- Now that I’m leading a team, how I’m trying to put those approaches into practice, and hopefully soliciting advice from you lot too…?

What is a Data Scientist really?

For a change, and with a certain sense of Irony, Google itself has settled on a pretty decent job description for the field;

“a person employed to analyze and interpret complex digital data, […], especially in order to assist a business in its decision-making.”

To me, this definition encapsulates three of what I think are the four key elements of what the modern Data Science role is, and it’s all the sexy ones.

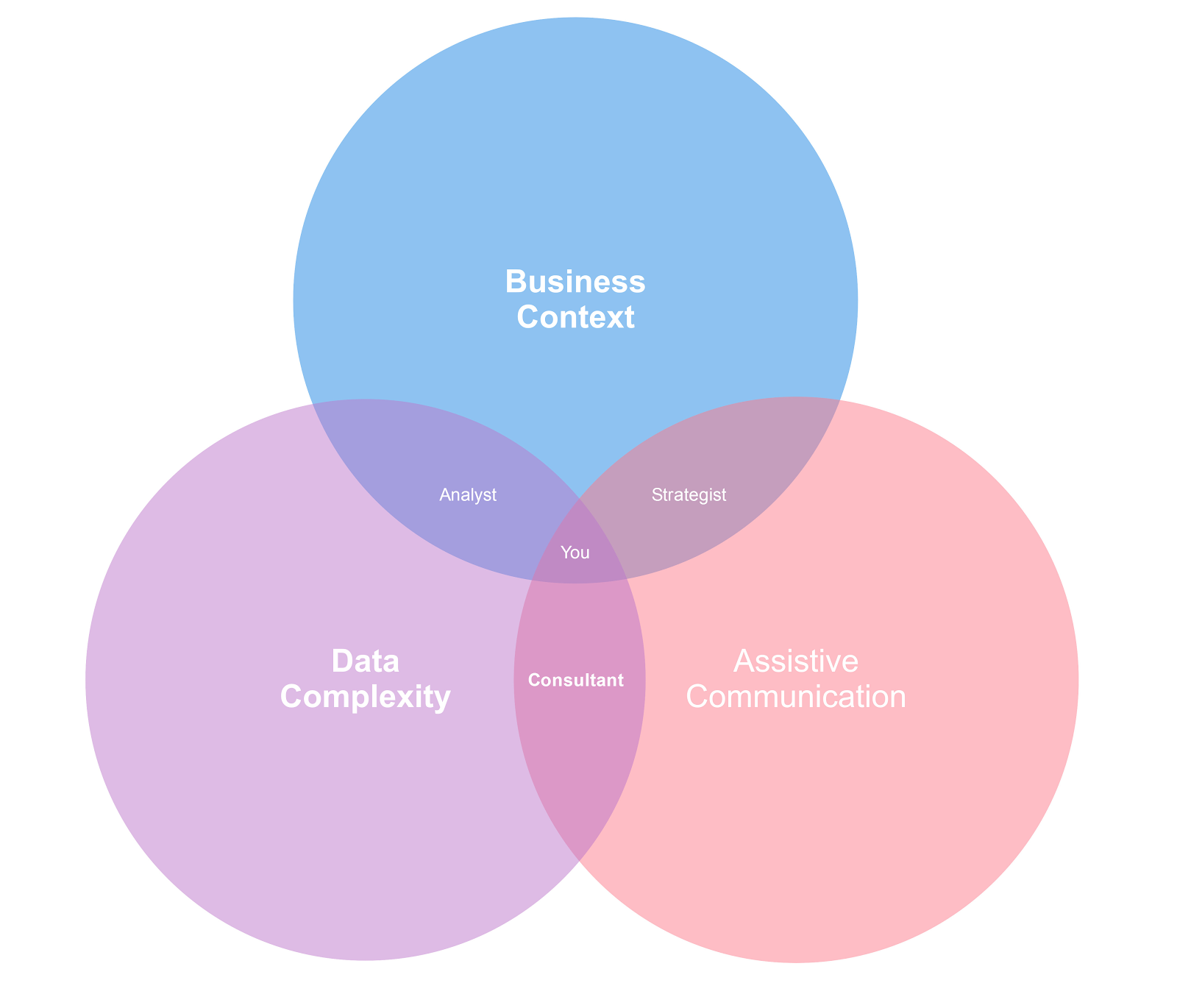

It says that Data Science sits in between Data Complexity, Business Context and Assistive Communication;

The obvious one is the Complex Data; you need to be familiar with how to access structured and unstructured data stores, you need to know how to navigate and validate your assumptions about that data, and be aware of techniques and methodologies to abstract or visualise that data.

A fairly common second highlight is the Communications aspect; at the end of the day, it’s your job to inform your internal and external customers with an appropriate amount of actionable information so that they can make an informed decision.

But, more subtly than that, you need to be aware of what the Business Context as a whole is trying to accomplish, not just the direct requirements that may be foisted on you. Some people call this ‘systems thinking’, I call it ‘caring about other people’s work as well as your own’, but each to their own.

As we’ll see later, this is often more important on the ‘interpreting’ side than on the ‘communication’ side…

Four is a Magic Number

So, we have Google’s Defined Trifecta of Complexity, Communications and Context, but I’d add in a fourth, but I think it’s quite overlooked in many ways. But in the interests of not breaking anyone’s brains, we’re going to forego the Venn diagrams in favour of Bullets…

- Complexity

- Communications

- Context

Anyway, what’s this fourth theme?

- Continuity.

Yes, it is a little bit of an alliterative backronym, but when I say Continuity, it has many meanings;

- Continuity of operations through automation and continuous testing.

- Continuity of visibility enforced by the construction of reproducible reports and continuous dashboarding pipelines.

- Continuity of meaning by the explicit and near obsessive transparency of recording and sharing assumptions, decisions, experiments, and most importantly, failures.

- Continuity of capability by having your Data Science operations actually survive your Data Science team being hit by a bus

So, in my contrived setup, we’ve now got Complexity, Context, Communication and Continuity.

Great, after 10 minutes, we’ve got a definition. Ish.

Great, move on Bolster; What does this all mean for someone either getting into Data Science as a career or building out a new capability.

Story Time

Before we get into the solutions, I’d like to share a couple of “WTF’s”, and then spend a little bit of time explaining where those WTFs actually came from.

I’ll avoid naming names to protect the guilty, but here’s a few beauts in no particular order. I’ll let you be horrified by them en-masse then we can spend a bit of time going through them to understand how these came about.

Exhibit A. The “Thing”

Once upon a time, a bright eyed data scientist was exploring a database. This was a mixed Perl PHP environment that had a lot of the business logic embedded in the production databases.

This isn’t a bad thing. What was a bad thing, was the ‘thing’ table that they discovered. A 6 way mapping table between different types of entities from completely different parts of the business logic, including user roles, scheduling specifications, and assessment targets.

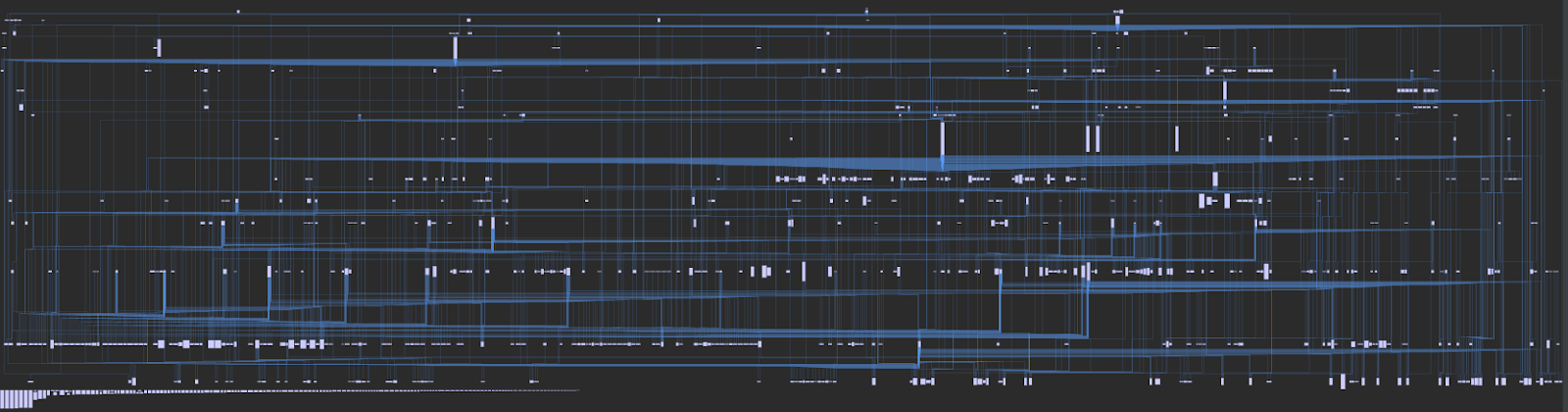

These were not ‘many to many’ relationships being maintained. No, my friends. This was to map a new global thing_id. A quick GitHub enterprise search for thing_idrevealed the horror that had been unearthed. Almost every interaction in the company first queried this table to work out what on earth a given query was talking about, leading to a structure that, after some coaxing, leads DataGrip to spew out this entity relationship diagram.

It’s easy to discount this as lazy engineering or an incorrect abstraction, but there are three things that, while they don’t justify leaving it that way, explain the history of how you could end up that way.

Factor one: long ago, there was no thing table; the company data architecture was built cleanly and there was no need for such hellishness.

Factor two: long ago, certain database’s Foreign Key performance wasn’t particularly great, so doing multi-entity ‘one to many’ relationships wasn’t all that fast.

Factor three: long ago, it was recognised that the company could expand some of it’s capabilities by acquiring a few other companies and integrating their data pipelines into theirs.

Now I think we can see the trouble. Long story short, an engineering department was under pressure to deliver on grand promises, and hacked together a solution that reused the previous clean data architecture in…. several different ways at once.

Exhibit B. A Role by any other name

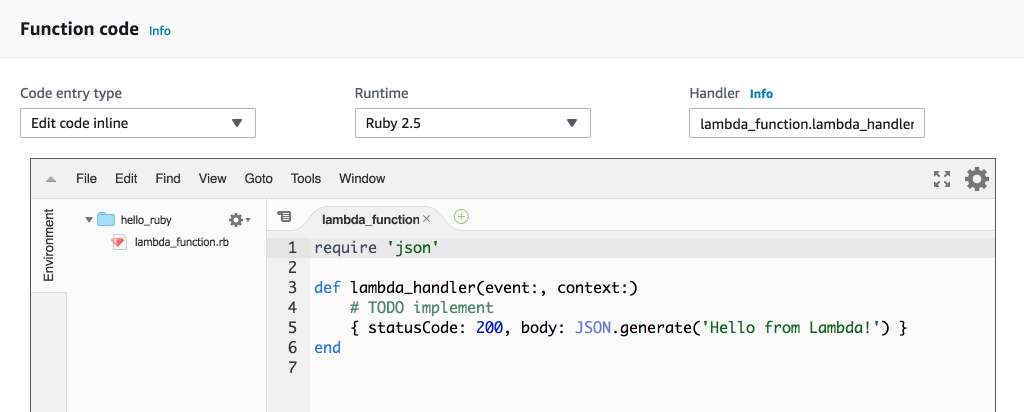

I was looking to deploy a data pipeline to automate something that had just been a cron job for ages. While I was still upskilling in AWS, identity management appeared to be a massive pain in the behind, so I decided to reuse an existing execution role, api_injest_ro, and considering this was largely an ingest project, that made sense. I reviewed the decision with my direct superior, who saw no problem with it.

On deployment, their pipeline died instantly as the entire company’s global client base started routing traffic through their, totally incorrect, pipeline instead of their primary ingest node.

This ‘isn’t really a story of a hack, it’s the story of subjectivity; one persons ingest is another persons… well, you know.

In this case, the role was not originally intended for API clients trying to read data from our own systems, rather it was intended for accepting data from external API clients sending data into our systems. This intention was not documented anywhere.

The hack was a frankly clever piece of early cloud load balancing where traffic was routed around the places that responded fastest with the least amount of non-200 responses.

Guess what was the only thing our intrepid data scientists pipeline template did?

(For the record, this is always a terrible idea; your code should fail disgracefully first….)

Exhibit C: What’s the difference anyway?

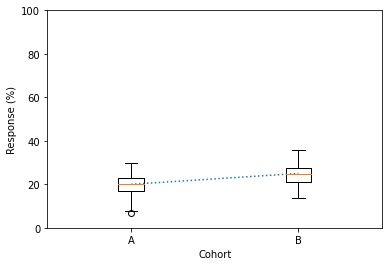

In another life, our friendly neighbourhood data scientist was doing a cohort analysis.

Participants in two different groups were put under different forms of stimulation, and the question was, what was the quantitative difference in response between the two groups.

Our scientist took the measurements, assessed the difference between the groups, and delivered the following two messages to the marketing team.

Group B responded 25% more than group A

Group B’s response increased by 5% on average compared to Group A

Time passes. The report is published, and then the calls start.

“Your numbers don’t make any sense? How can you have such a substantial effect? It’s physically impossible for a person to respond that much? You must just be making it up!”

Data Scientist goes to a website to read a completed report for the first time.

“This product increases

by 25%”

We can laugh about this now but this is a story of crunch timelines with a priority for speed over clarity, and no review or feedback opportunity for subject matter experts. Our data scientist gave two factual comments on the data from deep in their own trenches, and threw them over the no-mans-land into the editing trenches. This was then rushed out the door with little to no final review, and by the time the honest misinterpretation was revealed, it was clear that both sides had screwed up.

How do you solve a problem like Data Science

So, those are just a small sample of the challenges that face any data science team, but they’re doozies when you take them as abstract examples, and I believe that these examples at least could be ‘dealt with’ with some abstract advice.

- People don’t agree on what words mean, let alone what numbers mean, so don’t assume anything and add your assumptions to any numbers / statements you’re delivering.

- A Data Scientists’ job is not done once the number is out the door; you have a responsibility to make sure that whomever you delivered it to is on the same page as you as to its meaning

- Engineering, Strategy, and Innovation operate in tension with each other. Sometimes they speed each other up, occasionally they have to slow each other down. If a decision is made to do the wrong thing quickly instead of the right thing slowly, that needs to be a decision visible across that trifecta. And recorded…

That’s nice and all but how do you actually do that?

It’s been easy to stand up in conferences like this for years as an individual contributor, start-up data scientist, or solo-researcher and wax lyrical about how all the things that other people do is crap and it’d all be better if they just listened to me. It’s also fun.

However, how do you actually curate the kind of culture that I’m talking about? Both between a team, within an engineering division (your Data Science team is in your engineering division, right?), within a company and within a wider data ecosystem?

Well, I’ve been doing this for a year and I don’t think I’ve succeeded yet, but here’s some of the things that we’re doing in my team to try and foster this, with appropriate redactions made…

A Seat at the Table: As we’ve seen, the most challenging part of a Data Scientists jobs is often interpreting and ingesting from something that was never designed to be accessed in the weird and wonderful ways they want to. Data Science has to have a seat at the Engineering Architecture table, both to manage expectations and to highlight premature abstractions or constraints that might later cause a massive headache for analysis, but are simple to think about early on.

Transparency; Teams are encouraged to share both their successes and failures in the open with the rest of the company, and encouraged to discuss their work in progress openly in our team slack and to cycle in subject matter experts from across the company to contribute to the discussion, that way we can test our assumptions early and often so wether you’re a green horn statistician or a distinguished engineer, you can ask ‘stupid’ questions without any fear of backlash.

Bar-stool diversity: This is one of the only failures I’ve had so far in this role, where I started off being ‘given’ a pair of extremely experienced engineers who knew the platform inside and out, but not so much on the analytical rigour or the statistical operations. My first attempted hire was a talented neurobiologist. Unfortunately this was rejected above my head as they “didn’t have enough programming experience”. My internal response was “Yeah, doi, that’s kinda why I wanted them”. I ended up hiring a statistician who’d done some R and some Python. And proceeded to beat the R out of them. Anyway, back to the point. Data Science is a field that thrives on questioning and different perspectives, and if all you have is one leg, you’re gonna fall over.

Defended empowerment: part of my responsibility as a team lead is to give my team cover, both from management noise but also from vexatious questions; our team is doing great things because of the deep and wide knowledge embodied in it, and I don’t want to waste that strength answering questions from colleagues who haven’t read our reports or done any of their own research.

So I field those calls, and if I can’t point to a part of a report, document, or code that explains the question, I add it to my own to-do list to explain it and update the documentation, pending review from the original contributor.

So that’s it, that’s my principles for establishing and running a high performing Data Science team; get good diverse people, encourage their curiosity by giving them freedom to talk to anyone, encourage them to share their successes and their failures, and cover their ass from all the stuff that gets in the way, but make sure that their voice is heard at the highest levels as an equal partner.

And Finally

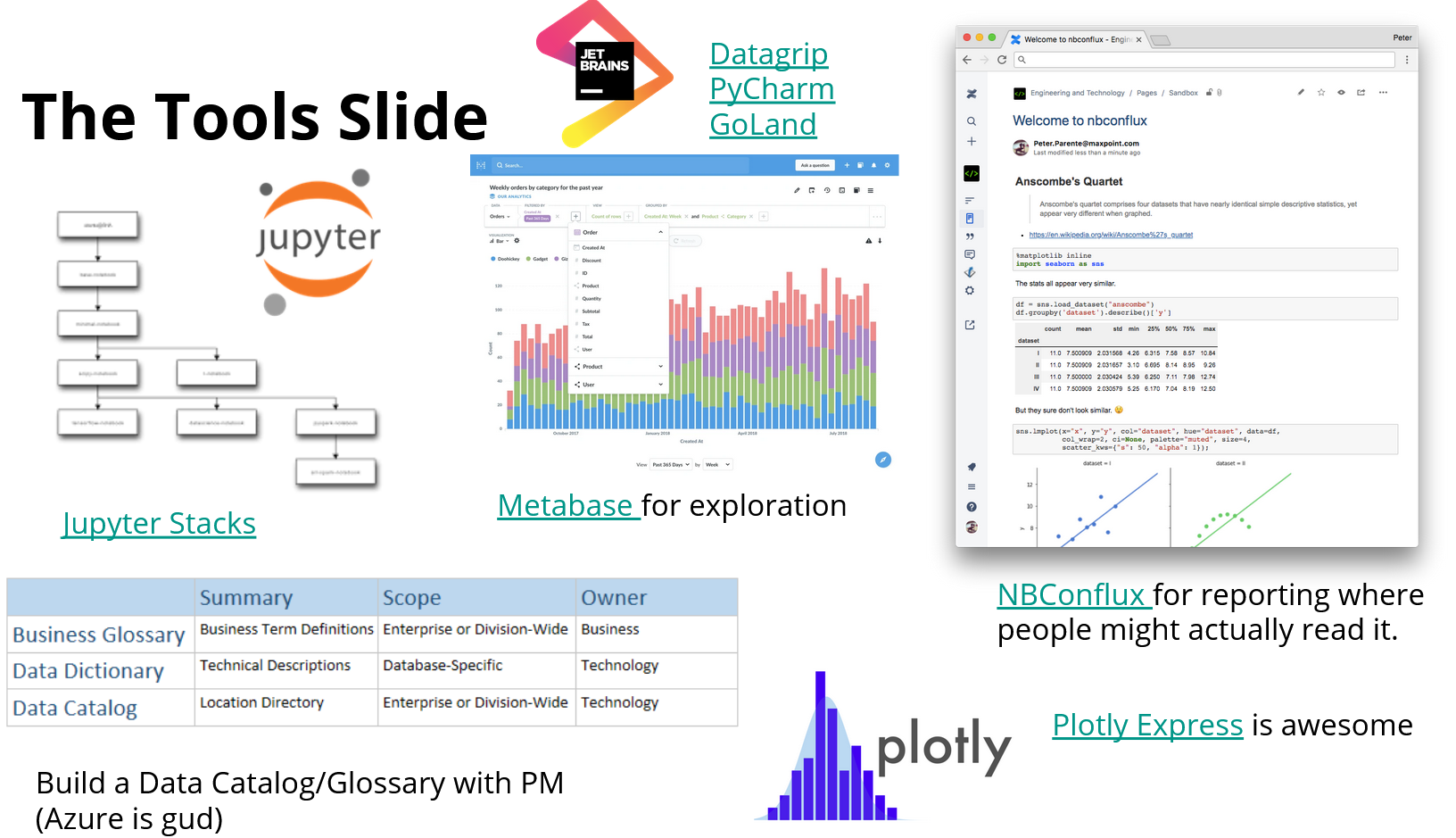

Just for those who wanted to get the Tools discussion, here’s my recommended stack;

- Jupyter Stacks running in Docker with folder mapping to userland for exploratory stuff, although my team are currently looking at moving all our exploratory analysis to Azure, and Azures Databricks looks like a drop in replacement, with the added benefit of the team being able to work in their own environments if they have a preferred stack themselves.

- Metabase for exploratory data collation as a team (also does particularly well at introspecting on what should be foreign keys but aren’t)

- Jetbrains DataGrip for, well, basically anything that it supports

- If you don’t have a data catalogue and a data glossary, you don’t have data. Azure Data Catalog is very good for both of these, including metadata tagging and the ability to make people outside your team ‘admins’ on particular terms. AWS Glue does similar but is more internally focused

- Pandas goes without saying, but I would flag that Plotly Express and it’s Jupyter integrations are looking awesome. If you’ve ever played with in notebook interactive graphing and found it frustrating, try it again.

- And finally, a personal favourite;

nbconflux, an extension to push Jupyter notebooks up to Atlassian Confluence, so that people outside your analysis environments can work out what the hell you’re talking about and what assumptions you made.

Final Thoughts

Data Science sits somewhere between Engineering, R&D, and Management.

Most people think it’s either magic or it’s going to steal their job or both.

For all the talk of Data Science being about technology, so far, for me, I’d had to learn more about the human side than the technical side.

But, as ever, your mileage may be non-deterministic.

Thank you for your time.