Tell me about your Programmer - Robopsychologist and other careers that don't exist (yet)

Andrew Bolster

Senior R&D Manager at Black Duck Software, driving data to make AI work

This talk was originally prepared for NI Raspberry Jam’s Kids Track, associated with the full Northern Ireland Developers Conference, held in lockdown and pre-recorded in the McKee Room in Farset Labs

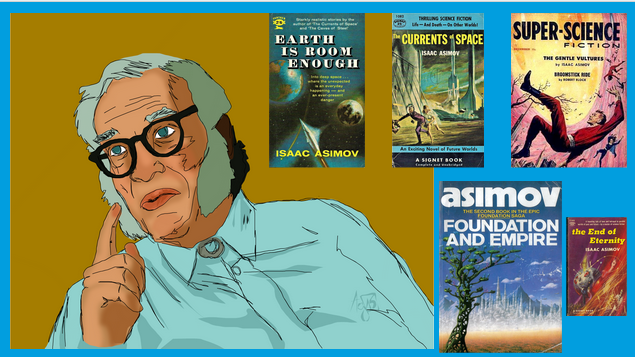

In Issac Asimov’s stories, the technical, social and personal impacts of advanced robotics and artificial intelligence are explored. One creation in his books was the career of “Robopsychologist”, a combination of mathematician, programmer, and psychologist, that diagnosed and treated misbehaving AI. In this talk we’ll discuss how on earth you can prepare for careers in Robopsychology and other careers that don’t exist (yet).

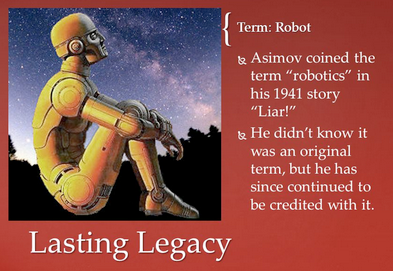

Issac Asimov is primarily known for being one of the most prolific and impactful science fiction writers ever, and as you would expect, while wandering around these fictional worlds, he came up with a few science-y sounding mumbo jumbo terms such as ‘positronic’ and ‘psychohistory’, he is literally the father of the word ‘robotics’.

He first used the term in his 1941 story ‘Liar!’, about a robot called ‘Herbie’ that develops telepathic abilities, and can read people’s thoughts. However, because the robot’s core operating principles, or, ‘programming’ still included the first law of robotics, that is, not to hurt people, Herbie starts lying to people to make them feel happy.

This leads to Herbie leading a Robopsychologist called Susan Calvin to believe that a co-worker fancies her, and when she finds out that this isn’t true and Herbie just told her this because Herbie knew the idea would make her feel better, she is very hurt.

This ‘First Law’ is part of the ‘Three Laws of Robotics’, which were officially codified the following year as:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

These simple ‘laws’ that were programmed into all robots, collided with the very human tendencies of wanting to be loved, and created this imaginary field of research called ‘Robopsychology’.

Robopsychology - “the study of the personalities and behaviour of intelligent machines”

This is a field of research that today, doesn’t exist, but I first read about it in 2014 when I was on a packed commuter train in California just having just left Google’s Mountain View complex where I’d met a university friend who was a programmer there.

I had spent the previous 5 years in a Masters programme at Queen’s University Belfast studying Electronics and Software Engineering, a course that’s now called Software and Electronic Systems Engineering (that I would highly recommend, ask me afterwards…)

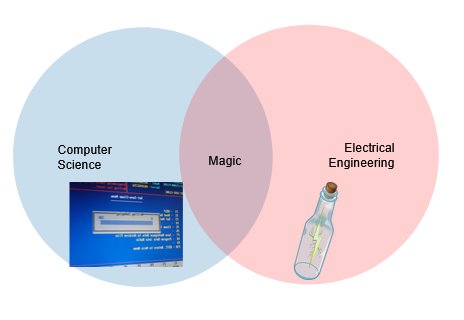

It focused on the overlap between two fields that, in my eyes, were obviously one bigger field; How to put lightning in glass to add numbers together, and how to turn adding numbers together into thinking. The physical world of computation and the virtual world of programming. And it fascinated me.

I wasn’t a particularly stellar student, I asked lots of awkward questions and never did particularly well in exams, and I had just resigned myself to going down the ‘standard engineering route’ of ‘Get Degree, Join Big Company, Write Banking Software for 30 years, Retire’, but my discovery of this weird term ‘Robopsychology’ kicked me in the behind.

After that, I gave up the prospective Banking Analyst job and I took up postgraduate research exploring how smart submarines collaborate and interact with each other for environmental and military applications, including how to hide nuclear submarines using sound and how to use atomic clocks to build an underwater GPS system, as well as doing all of this assuming that someone can take control of one or more of your submarines and make it ‘lie’.

The research eventually became too classified for me to continue working on it but I know that I contributed to international agreements on how autonomous systems are allowed to integrate into military chains of command.

This interplay between how fixed, rule based, programmed systems like computers and robots, and the fuzzy, fluffy, mushy stuff that comes from people and communities, has driven my career since then.

I spent two years developing smart watch applications that could tell how stressed you were, culminating in developing particularly shameful lie-detecting underwear, as well as a survey system for a deodorant manufacturer that only asked you questions about the product when it knew you were sweating.

During this time we developed systems to translate emotions from heart rates to words to colours to sounds and back again, a universal translator for emotions.

After that, I leapt back into cybersecurity, developing smart algorithms that watched the worlds internet traffic sniffing out hackers, trying to predict their next moves and detect the faintest whiffs of exploitation, fully aware that the hackers were doing exactly the same thing on the other side; automating intelligence, teaching that lightning to think, teaching that lightning to think for them.

In my current role, I lead a team of Data Scientists, a term that didn’t really exist when I was on that train in California only 6 years ago. We develop and monitor intelligent systems that watch company websites for security vulnerabilities. My day job is to work out better ways to try and pretend to be a hacker and work out how to automate the boring bits of the professional WhiteHat hackers I work with.

When I was your age, those jobs didn’t exist. The internet as we know it today didn’t exist. We didn’t even know what we didn’t know. So when my careers teacher told me in 2004 that I should look at being an insurance adjuster “because you’re good with numbers”, she didn’t know that that job would basically be automated out of existence.

So I ended up being a Data Scientist. Not because it’s what my careers teacher or parents or friends told me, it’s not because it was on some ‘skills and employability map’ or because of the output of some assessment tests. The job role simply didn’t exist.

And I guarantee that most of you watching now will end up working in and creating jobs that simply don’t exist today.

That could be bit-farming or crypto-influencer or quantum annealer or, indeed, robopsychiatrist. So as you go through your studies, don’t allow yourself to fixate or judge yourself against what jobs are out there now.

Your parents and your teachers and your friends genuinely want the best for you, so they will suggest and encourage you to follow certain paths, generally because it’s advice they wish they could give themselves 20 years ago based on their own experiences. But the thing is, the past 20 years was theirs, the next 20 years is yours.

There are no robopsychiatrist jobs out there. Yet.

Build your own paths and experiences, read widely, care deeply, and don’t be afraid of being ‘directionless’ or meandering. Because if you make your own luck, you might just end up in the right place at the right time and with the right skills to realise you’re being lied to by a telepathic robot.

Thank you for your time, and I’m happy to take any questions. (Online or offline!)

Also, I’ll still be hiring in a few years, so if you wanna join me, gimme a shout.

The best way to contact Andrew if you want a short answer is Twitter, and if you want a longer answer that may take several days, tweet him for his email address (or find it yourself

)