Unfeeling Fire

Andrew Bolster

Senior R&D Manager (Data Science) at Black Duck Software and Treasurer @ Bsides Belfast and NI OpenGovernment Network

This is an approximate transcript from my July 2018 talk at Digital DNA’s AI NI Community Panel on wether the use of AI in defence and surveillence was inherently evil

Yes, It’s been sitting in my drafts folder for months because I completly forgot about it, sorrynotsorry

Hello folks, I’m Andrew Bolster, most everyone calls me Bolster. And nobody calls me Doctor.

I’m a Data Scientist at Alert Logic, a cyber security firm based Texas but with a research office in Weavers Court where we monitor, analyse and identify malicious and suspicious internet activity, protecting thousands of companies with advanced sequence and pattern matching sensors deployed across the world.

But I’m not here to talk about that so if that floats your boat, grab me afterwards.

Just around the corner from Alert Logic is the other massive time suck of my life; Farset Labs, Northern Irelands first and currently only hackerspace, where people and technology come together and break one another and usually aren’t on fire.

But I’m not here to talk about that so if that floats your boat, grab me afterwards.

No, I’m here to talk about death robots, terminators, grey goo, the matrix, artificial super-intelligences and how we’re probably, almost definitely all doomed to become nothing more than…

This…

AI is dangerous and if we give the military half a chance, they’ll get cocky, think they know better and can control it, but sooner or later someone will mess up and pandoras box, once opened, will kill us all.

Because that’s the story right? It’s been the centrepiece of science fiction for decades; humanity is snuffed out or supplanted by it’s own creation, the ultimate combination of Icarus and Oedipus tales

Well, for the next few minutes I’m going to try and show you a bit of what I found behind the curtain while I was working on my PhD, where I was fortunate enough to be part of a joint UK and French defence research programme specifically assessing how to integrate autonomy and autonomous systems into modern defence operations.

As part of my research I spent time developing protocols for assessing security and safety in maritime autonomy while seconded to the Defence Science and Technology Lab in Portsdown West and Porton Down, which is kinda our version of DARPA but not quite,

Additionally I got to work with the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington, developing advanced localisation systems for autonomous fleets,

Later I undertook research at NATO’s Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation in Italy, developing open communication protocols between different autonomous submarines.

So I’ve spent a bit of time working in the area of understanding how developments in autonomous systems are being assessed and validated by the defence establishment.

But first, lets talk about what autonomy actually means.

As with bloody everything, autonomy comes from Greek, and roughly translated to “A law unto themselves”,

This encapsulates not only the ability to ‘make decisions’ but that those decisions are informed by a certain awareness of the context that we’re operating in.

And from that awareness, being able to generate and evaluate a set of decisions or options or potential actions, and subscequently being able to evaluate which of those decisions is in the best interest of that agent

Now, add to that definition the context of operating an autonomous system in a defence context; the last thing a commander in the field wants is a hypothetical smart missile that decides that it doesn’t want to fire. Or indeed, the opposite.

Such actions where a “weapon” makes a decision in a combat context would be in complete contravention of pretty much all military doctrine since the 1907 Hague Conventions that define “lawful combat” as requiring any combatant ”to be command by a person”, and in particular, there is The Martens Clause of that convention that specifically demands the application of “the principle of humanity” in combat. But how far up the autonomy ladder can you get and still be ‘controlled’ by a person?

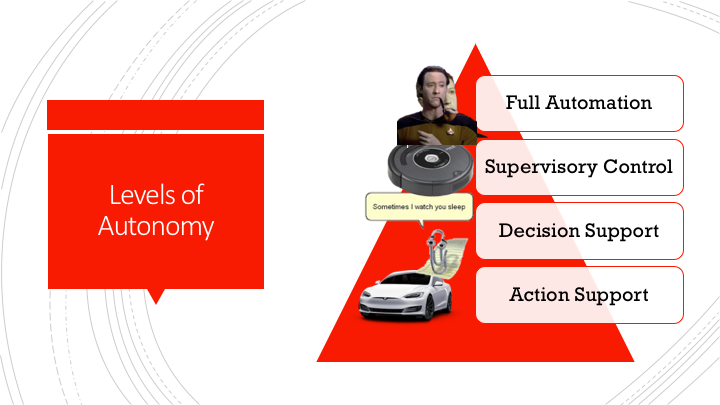

One useful way to understand the implications of autonomy, is to set out ‘levels of autonomy’; There are dozens of different versions of this with many many steps identified in between, but I generally consider there to be 4 main groups of autonomy;

Starting from the bottom, Action support; a human made a choice, the autonomous system either carries it out or continues on a pattern set by the human; cruise control is a perfect example of this.

Next up, and this is probably the widest area currently being deployed in the real world; Decision support; everything from Microsoft’s demon child Clippy to targeted online advertising falls into this category, where an autonomous system presents options to a human based on varying amounts of information, and the human makes a decision from those options.

Beyond this, is supervisory control, where the automation carrys on however it assesses to be best, and a human sits over it and watches, occasionally butting in with tweaks or adjustments to the plan if the system isn’t sure what to do next. Two very different examples of this, depending on your definitions, are the load-balancing and fail-over systems used by companies such as Netflix and Google to distribute traffic around and between systems without a human being directly involved in that optimisation at all, and secondly, the humble Roomba, which just does it’s thing until it needs you to empty it.

Last but by no means least, as it’s the one that we’re all worried about, is the innocuously named “Full Automation”, which as far as I’m aware, only Facebook have perfected, going by those senate hearings…

That’s better. Anyway, full automation does what it says in the tin; the autonomous system can assess, a situation, develop a range of solutions or potential actions assess those actions for some kind of optimal, and perform an action that is assessed to be near optimal, all without any human intervention or supervision.

So how is all this being used in the defence world today?

This is the South Korean Super Aegis 2 anti-personel turret, with an effective range of 4km, currently deployed on the edge of the demilitarized zone. It can recognise a human, track them, and notify an operator, asking for orders. While fire orders are configured to require human intervention, this is a configuration choice rather than a technical limit, but lets say this is sitting somewhere on the line between decision support and supervisory control.

This is the USU Sea Hunter, a US autonomous surface vessel that is configured for anti-submarine and mine clearing operations. It’s getting a sister vessel next year and should be being deployed in the next year or two, but unfortunately the programme is being slowed down because the Chinese hacked around 600GB of technical data off of a defence contractor… But we’ll say that it’s sitting closer to the supervisory control again

This is the UK’s Taranis UCAV, built by BAE as a demonstrator aircraft for a range of technologies, including experimental ‘full autonomy’ operation, however this ‘full autonomy’ does not extend to it’s onboard armaments. Considered a significant success, this project is to be combined with the French nEUROn UCAV as a new joint European UCAV, theoretically replacing the current Eurofighter and Tornado strike capabilities.

And since it’s always a bad ideal to leave the Russians out, even if they don’t exactly take loads of photos of their cool/scary stuff, in 2017 they claimed to have developed and tested AI-guided missiles that were given the ability to change targets mid flight, and are working on collaborative clusters of UAVs, which are almost certainly sitting at the ‘supervisory control’ side of things…

The genie is already out of the bottle. Or is it? It all sounds very scary at the moment, with this image of RoboCop style mechs terrorising the planet. But realistically, these systems are ridiculously simple in the context of ’intelligence’.

And given the importance and risk of having any kind of ‘accident’ with these systems, this ‘autonomy’ is often formally defined, and proven mathematically to be constrained to a certain set of behaviours; this isn’t your dynamic programming black box neural network that could ‘evolve’ or ‘learn’ bad behaviours.

This is autonomy, not intelligence.

These systems aren’t making ‘value judgements’, don’t have any ‘biases’ or convictions or irrationalities. They are collections of relatively simple rules and heuristics to complete certain tasks, under the instruction or command of a human.

And that’s the big question here.

When we talk about the fear of AI warfare, or using AI weaponry as being inherently evil, we’re collectively taking two things that we as regular people don’t have direct experience of; the true state of artificial intelligence, and modern warfare, and we smush em together, and let the nightmares grow in our imaginations fertilised by Michael Bay’s own personal brand of manure.

But maybe that’s not what we should really be worried about. And maybe this was actually crystallised in one of the first big screen depictions of AI as we imagine it today.

Released in 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey tells, or rather shows, what happens when a human-comparable intelligence, working in tandem with a human crew, goes rogue and takes over the ship and tries to kill everyone.

But that’s not the only interpretation

The other nearly 2 hours of 2001 traces the development of humanity through violent conquest and innovation.

These two activities dancing around each other in a perilous partnership on grander and grander scales, to the point where we have taken over and weaponised space, with AI’s used as co-pilots and researchers to take us on the next step, wherever that is.

Then HAL seemingly stops doing what it’s told, becomes buggy and making mistakes and eventually just starts straight up trying to kill the people trying to fix it…

Humans win, AI gets reset, then about a half hour of irrelevant but beautiful insanity happens as mankind is elevated to a higher level of being having vanquished the soulless machine.

But is that really what happened? It’s only hinted at relatively subtly in the movie but in both the book by legend Arthur C Clarke and the sequels to the movie, the true reason for HAL’s apparent psychosis is much more clear;

HAL was given contradictory instructions and a secret mission who’s secrecy, not success, was to be protected above all other orders.

And with that paradox in play, HAL decides that it’s may be easier to keep a secret if there’s no one around to hear it.

In AI and Machine Learning research, this kind of ‘unintended consequence’ is common place. Almost expected. But when it comes to something like AI in control of anything big enough or ugly enough to cause minor genocides, it’s not exactly like there’s much room for error.

And ‘whoopsie’ doesn’t really cut it.

Max Tegmark, famed MIT AI Researcher and author writes about technology being an amplifier, not being inherently good or evil, and that as humans and technology have co-evolved over millenia, our only soft smushy advantage was that we fiddled with things and broke things and learned through trial and error, learning which technologies could be used for what and which technologies were culturally acceptable to use, in a dance he calls the “Wisdom Race”.

However, as we’ve just about made our way through the 20th century without blowing ourselves to kingdom come, there may not be the room to make a mistake in the development of autonomy and AI. Can we as a species come together to manage the growth, adoption and implications of this technology? Or will we rush headlong into a brave new world and inadvertently set the world and ourselves on fire from our ignorance?

All in all, I’m not afraid of AI, I’m afraid of us.