So, what is it you do again?

Andrew Bolster

Senior R&D Manager at Black Duck Software, driving data to make AI work

Update: I got asked to do a simplified version of this post for the University of Liverpool, it lives here (Backup)

I’m technically in a third year of a PhD, and most of the time, when someone asks me what it is I’m actually doing, I fluff it and say something about “autonomous submarines” or “collaborative autonomy” or “Emergent properties of communities” or something similarly vague.

In the spirit of setting the record straight in a less-academic way, I thought it’d be worth while to edit a presentation I recently made to the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence last month in Stanford and make it a little more digestible.

I’m always happy to discuss the ideas, impacts, or problems with my work, especially from strange and wonderful angles, so gimme a shout on any of the normal ways!

Introduction

I’m a PhD Researcher at the University of Liverpool working with Professor Alan Marshall in the Department of Electronics and Electrical Engineerings Advanced Networks Research Group. I’m going to try my best to explain some of the work we’ve been doing in the area of developing a multi-vector trust management framework for collaborative operation of autonomous systems, as summarised in the paper.

Specifically, we’ve been looking at the relationships between physical behaviour and communications behaviour within teams of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) for uses related to mine counter measures and port protection for defence, as well as persistent survey behaviour for environmental and petrochemical applications.

What is Trust

To begin with, it’s important to clarify what we’ve considered to be the definition of “Trust”. It’s a word that gets used a lot in many different ways.

Merriam Webster’s Dictionary defines trust as “assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone or something”, and this rather far reaching definition is very attractive to distributed network design as an invaluable area of information to inform autonomous actors, or nodes, to the ‘best’ courses and paths to action.

Within this context, we define trust as “The Expectation of an actor performing a certain task or range of tasks within a certain confidence or probability”. In the real world use-case of deployable autonomous systems for survey or other application, this trust can take on two real forms;

-

Design Trust, where there is an expectation that a system of systems will perform as specified or designed in operation, and

-

Operational Trust, that is that the individual systems within a larger system will and are performing as designed in the field. It is this area with which we are particularly concerned.

This desire for operational trust in mobile ad hoc networks has lead to the development of several Trust Management Frameworks, where such frameworks provide information regarding the estimated future states and operations of nodes within such a network. As such, the operation of such frameworks is summarised by Li and Singhal as “ collecting the information necessary to establish a trust relationship and dynamically monitoring and adjusting the existing trust relationship”

As an aside that didn’t make it into the final talk, all of the organisitional trust and management assurance in the world will not save you, as indicated by this extremely complex graph of the US Nuclear Deterrant

Trust Networks

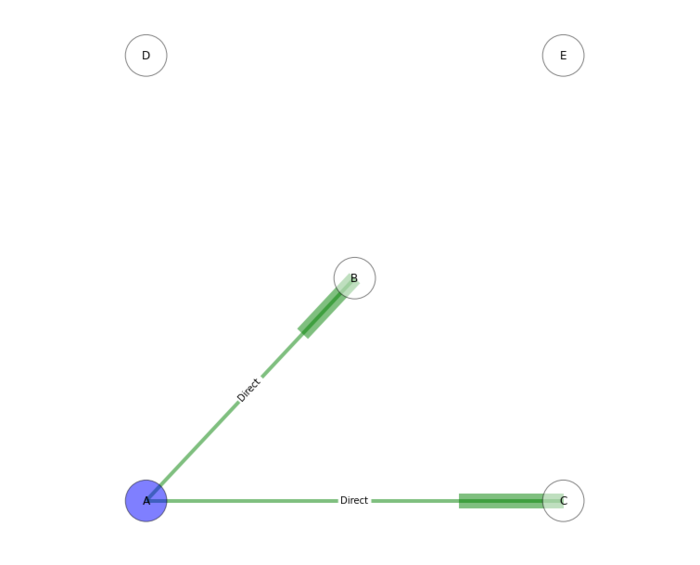

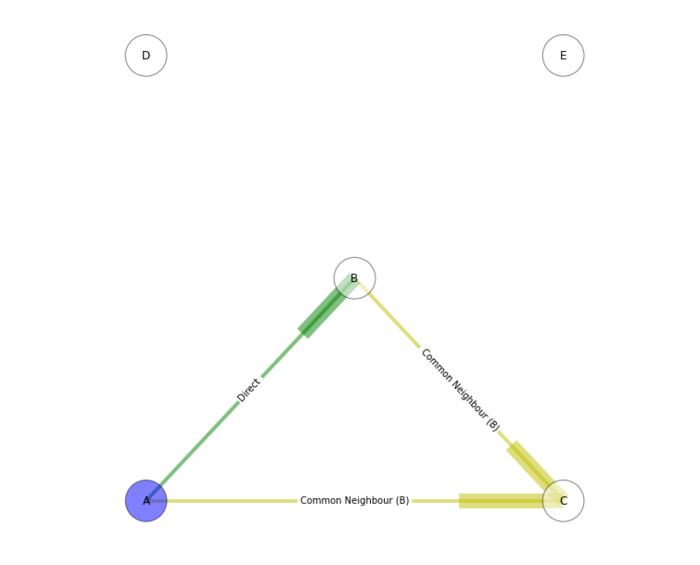

These frameworks have historically operated exclusively on the historical communications behaviour of the nodes, but some also take into account the implicit transitivity of trust within sparsely connected networks, combining direct observation, common-neighbour recommendation, and indeed indirect reputation.

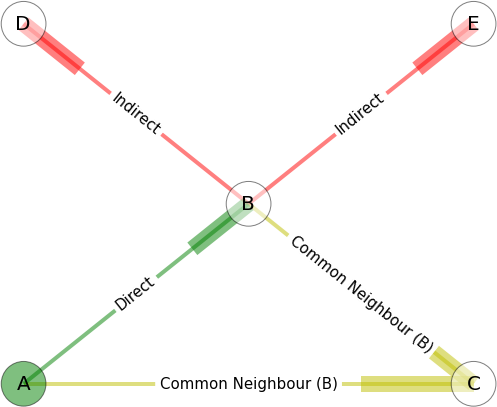

These spanning relationships can be demonstrated in their simplest form in this diagram. Speaking from the perspective of Node A in green on the bottom left, we can see that there are direct relationships with nodes B and C, representing a potentially asymmetric communications link with those nodes. However, due to the direct connection between nodes B and C, there is additional information about the trustworthiness of node C by A taking account of B’s broadcast opinion of C. There is also a similar recommendation relationship between A and B, by transiting through C, but for the sake of simplicity that is not shown on this graph.

In the third case, nodes D and E may be completely unknown to A, or may have previously had a direct relationship with A but no longer do due to a change in network topology, however we can still garner some information about their trustworthiness indirectly through effectively ‘taking B’s word for it’.

In the real world of mobile ad hoc network, such relationships are dynamic, and may be asymmetric, in that for instance, A may be able to observe C’s behaviour, but C cannot observe A’s. This transitivity also facilitates the reliable introduction of ‘new’ members to a network via partial-stranger operation, as demonstrated in Evidence or Certificate Based Trust through credential sharing,and Monitoring or Behaviour based trust, where new nodes effectively sit in low-priority ‘limbo’ being observed before they’re brought into the ‘in’ group.

The real question however, is what’s the point of this concept of trust and how is it generated, shared, and reacted to? These questions are what the bulk of my research has been about.

First off, in terms of the ‘Point’, this concept of Trust is useful for informing node-internal processes to efficiently engage with the rest of the network. This informed decision making can sometimes closely mirror our human concepts of societal and group trust, such as Phone Tree’s being used to share information along the strongest most reliable routes, or Shunning people who have been observed misbehaving. It can also be applied not only to the routing of information but the processing of that information, in the same sense that you should all have a healthy sense of skepticism about everything I am saying since none of you know me particularly well and I don’t have a massive reputation.

Finally, an operation of most Trust Management Frameworks is the decay of Trust assessments, meaning that if a previously ‘red flagged’ node behaves well for a long period of time, it can be ‘forgiven’ and likewise, a node that was previously trusted will have that trust reduced over time if it does not continue to meet expectations.

These behaviours taken together can provide powerful risk mitigation against a large family of network-based attacks such as Black and Gray hole attacks where packets are selectively dropped based on timing or the node sending a packet, causing that sender to be observed as a ‘bad node’ by the rest of the network, or attacks on the optimality of the routing structures of the network, or simply being selfish and not playing ball with the rest of the group.

Trust assessment and multi-metric sensing

As stated, most existing Trust Management Frameworks are predicated on the communications behaviour of the nodes within the network, or by explicit certification by a central or trusted authority at runtime in the case of PKI and Resurrecting Duckling, or in the case of Evidence Based Trust, having a pre-shared cryptographic key provided a priori to deployment. While these are all valid approaches, the reliance on a centralised or pre-defined authority provides a weak-spot in the networks security if that ‘authority’ is subverted, hence the justification for the use of a truly decentralised Trust Management Framework such as CONFIDANT as proposed by Sonja Buchesgger1, which was based on layering trust assessments over Dynamic Source Routing, or Objective Trust Management Framework as proposed by Li in 20072, which led the charge in terms of using multiple values to categorise trust, in this case ‘trust’ and ‘confidence’.

However, until Bella Guo presented her work3 on Multi Parameter Trust 2 years ago, very little had been done to look at more than a single observation, with packet loss rate being the historic frontrunner of observations.

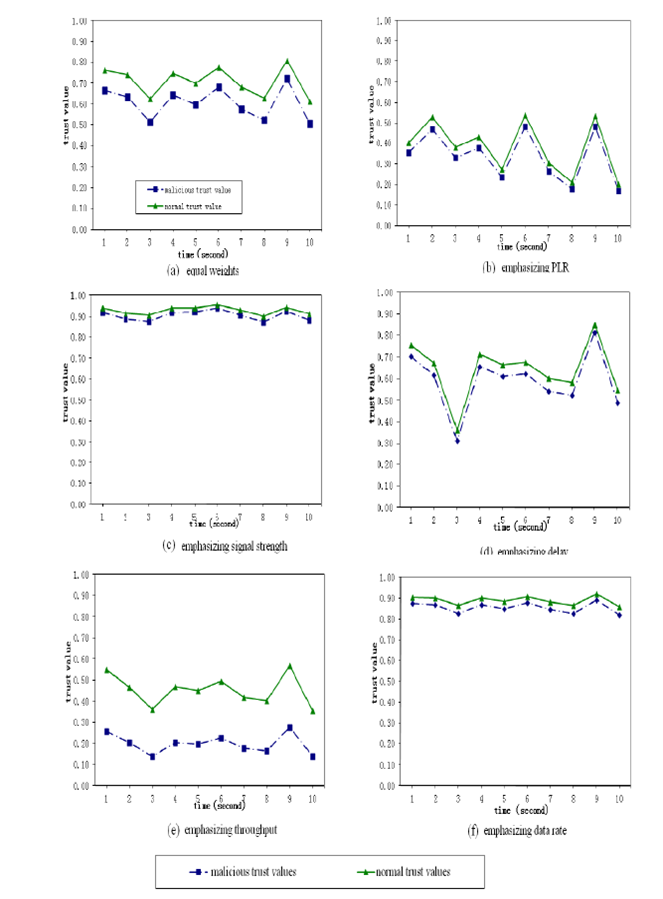

\[X=\{packet\ loss, signal\ strength, data\ rate,\ delay,\ throughput\}\]She presented a methodology based on Gray Theory to take multiple, mostly independent metrics such as packet loss rate, signal strength, datarate, delay, and throughput, to form a single trust assessment in the form of a vector, with trust being assessed by a weighted interval of these metrics. Previous to this some TMF’s had treated trust as a stochastic description of trustworthiness in the form of a trust value and a confidence value, conceptually identical to the average and standard deviation of a distribution.

\[\big[\theta_{k,j},\phi_{k,j}\big]^t=\Big[\frac{\min_k{|a_{kj}^t-g_j^t|+\rho \max_k{|a_{kj}^t-g_j^t|}}}{\max_k{|a_{kj}^t-g_j^t|}t},\frac{\min_k{|a_{kj}^t-b_j^t|+\rho \max_k{|a_{kj}^t-b_j^t|}}}{\max_k{|a_{kj}^t-b_j^t|}t}\Big]\]This Gray interval in it’s long form is an exceedingly ugly construction but can be viewed as the lowest (\(g\)) and highest(\(b\)) expectation value for an actor \(k\) observed performing action or metric \(j\), scaled against the observed range of behaviours in the rest of the cohort, meaning that in an efficient trust network, these intervals should be similar across each node.

\[\big[\theta_{k},\phi_{k}\big]^t= \sum\limits_{j=1}^m h_j \big[\theta_{k,j}^t,\phi_{k,j}^t\big]\]In order to coalesce this multi-metric vector of intervals, a simple weighted sum is used across each high and low expectation based on an Analytic Hierarchy Process where metrics are pairwise compared, either by field experts or through a machine learning process against known bad behaviour sets, grading the relative importance of each metric towards bad behaviour, however the system4. We’ll come back to this weighting function in a bit.

What we’re left with is a per-node interval of trust, which again, in a well performing network, should be relatively close in their bounds.

\[T_k^t = \frac{1}{1+\frac{(\phi_k^t)^2}{(\theta_k^t)^2}}\\ T_{k,tot}^t = T_k^t + T_{k,net}^t + (\alpha \times T_k^{t-1} + (1-\alpha) \times T_{k,tot}^{t-1})\]When this trust value in then weighed against the recommended and potentially indirect trust assessments of a nodes peers, as well as exponential smoothing against recent trust values, a final trust assessment is constructed for the timeframe.

Going back to that weighting function we glossed over a minute ago, the beauty of MTMF is that once a misbehaviour has been detected by comparison with other cohort intervals, the form of the misbehaviour can be identified by applying a range of weight vectors to the metric vector, enabling nodes to not only detect that the network is operating sub-optimally but to identify in what measurements a node is subverting the network and to potentially react accordingly.

Our main goal in this project has been to investigate if the methodologies that Guo applied to communications, can equally be applied to physical behaviour. Our approach to this has been to develop an agent based simulation platform built in Python, emulating both the physical and communicative environment for teams of flocking nodes performing some task, such as mine counter measure survey, port protection, mother-ship protection and others.

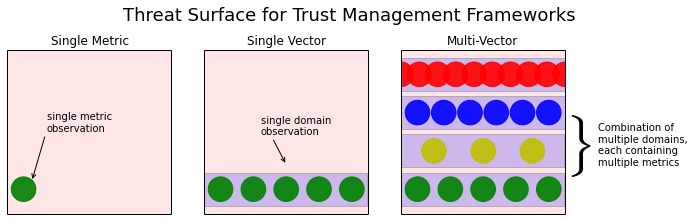

This interaction in the physical world opens up a range of metrics that can be used for trust assessment, in an effort to further restrict undetected malicious behaviour on the exposed threat surface of a network.

In single metric trust, such as the use of packet loss rate in other TMFs, this only detects a relatively small area of the potential attack space. Combining several domain specific metrics, in this case in communication, provides not only the capability to detect a much wider range of attack types, but also to discriminate between them, informing of the tactics of an attacker.

Our hope is that by using multiple domains together, we can provide a higher level, strategic point of view on an attacker or attackers, enabling the generation of preventative and reactive strategies to defend against them.

Through collaboration NATO’s Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation based in Italy, and the UK’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, we settled on a range of observable metrics based on the position and attitudes of other nodes in the group.

These were;

-

The Inter Node Heading Deviation, i.e. the deviation in heading from a local group average,

-

The Inter Node Distance Deviation, i.e. the deviation of a given node’s position with respect to the average node spacing across the rest of the local group,

-

And The Node’s Absolute Speed.

Along with metric selection, we also arrived at a few sample ‘Misbehaviours’ covering both malicious and non-malicious non-optimal behaviours which were simulated in the framework. These were:

-

The Shadow, where a node is following the fleet without appropriate mission knowledge such as the waypoints in a patrol path, modeling an ‘infected’ or masquerading node in the fleet

-

The SlowCoach, where a node is operating correctly but has a defect in it’s power train causing reduced maneuverability, i.e. a runtime defect in an otherwise ‘good’ node

-

The Spy, where a node consistently or intermittently rises to the top of the fleet, potentially surfacing to relay mission information to an unauthorised third party via a backchannel communications channel such as RF

-

The Sloth, where a node is selfishly conserving energy by not making complete patrol paths or consistently taking a minimal path around the tolerances of the waypoint path

We’re also working on a few more that aren’t ready for primetime, and in the interests of timekeeping we’ll only concern ourselves with the Shadow and Slowcoach behaviours, as this presents a useful side affect of trust based on physical behaviour; the ability for a network to self-test it’s health by discerning the difference between broken and malicious behaviour.

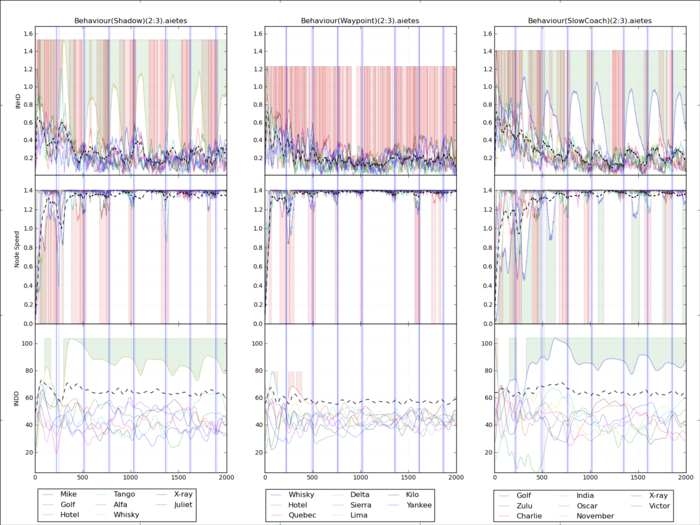

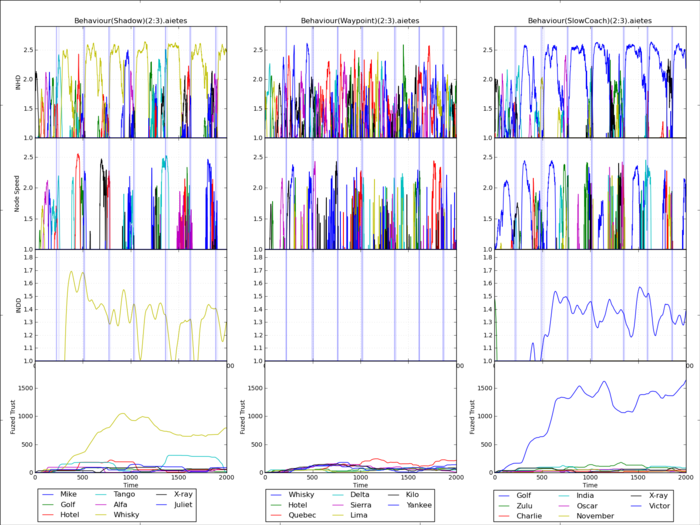

In a simple port protection scenario, where nodes are patrolling around a series of waypoints around an area, We can demonstrate this selective power through a series of frankly horrible graphs that if anything justify the abstraction of such metrics into a trust value.

Each vertical of this chart shows a different behaviour; with the baseline waypointing behaviour in the middle, flanked on the left by the malicious “Shadow” behaviour and on the right by the benign but sub-optimal “Slowcoach” behaviour. The per-node metrics as described are shown in the horizontal, with Internode Heading Deviation at the top, Speed in the Middle and Distance Deviation at the bottom.

Green shaded regions are correctly detected per-metric deviations, and Red shaded areas highlight sections of the graph where a per-metric “false positive” would have been reported, i.e. a normal node deviating outside the limits of that metric. Looking at it, it’s a mess.

This second graph shows the proportional deviation from the average of each metric rather than the raw values for the first three row, which is significantly clearer as to who is misbehaviour, especially in the case of the Inter node distance deviation, which shows the yellow and blue nodes respectively as being outliers. Applying the trust assessment as described previously, to the bottom row, of the chart, we can see the benefit of the exponential window on the false positive rate.

With this chart it’s possible to see, despite the colour and resolution, that the slowcoach behaviour manifests itself in the Speed metric as we can see here and here. Using this information we can build a trust weight vector to discriminate between these two ostensibly similar behaviours. With our current analysis we can do so with an average 97% positive identification rate with no false positives, i.e. no instances where a Slowcoach is detected as a Shadow and visa versa.

Cross Domain Analysis

We’ve established that communications trust assessed using a Gray theoretic comparator can discriminate between bad behaviour in the Communications domain, and that the same methodology can be applied to the Physical Behaviour domain. Now the question is can we do the same thing across vectors, mixing Physical and Communicative Trust to detect and identify behaviours that may be permissible in both domains separately, but not when looking at both. This is the question that we are currently working on, and our first step in this is to assess the challenges of creating a multi-vector trust framework.

Primarily, these boil down to the major issue of identifying behaviours that ‘pass’ both domain trusts individually but manifest in the interaction between domains. The short answer to this is that we have not demonstrated any as yet, however one behaviour mode that is a prime candidate for this is a sister to the previously mentioned “Spy” behaviour where a node ‘nips out’ for a while to transmit on a secondary communications channel. We are currently working with our partners to validate the practicality of such an attack on the network. If anyone else has any ideas I’m more than happy to discuss it afterwards!

However while we cannot yet demonstrate a cross domain attack, questions remain as to the practical operation of a cross domain trust framework.

-

Given the complexity of cross domain behaviours, how can network efficiency and optimality of operation be defined and monitored?

-

Given that we haven’t yet created a real cross-domain behaviour, is there a point? From an aesthetic position I strongly believe there is. But even so, while we’ve settled on Gray coefficient abstraction for vector level trust, is it optimal to raise that to cross domain trust?

-

Can metrics from multiple domains simply be combined into a single vector rather than abstracting further?

Other Stuff

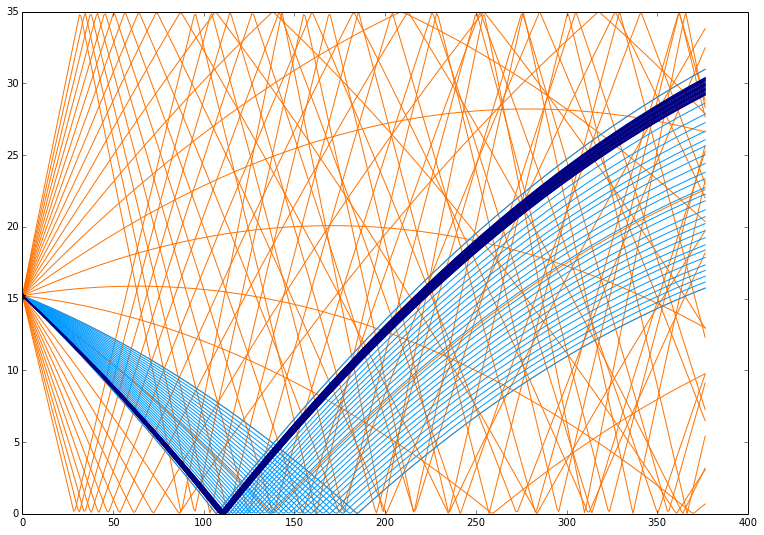

Aside from the Trust research, UUV Kinematics applications, simulation blahblah etc., I’ve also been working on collaborative positioning system for submarines, using shared-time-state statistics using Time of Flight to estimate the least squared geometry of the fleet in motion. This is already long enough but I’ll just share one image to highlight that this is a pain; the below is a snapshot of a single monte-carlo ray-tracing phase of an acoustic wave passing through water between two nodes. This contains roughly 200 paths, depending on the setting, and has to be recalculated on every message on every node to every other node at every timestep (where there is a transmission).

The curve is due to variation in the speed of sound in water at varying depths, so the ‘shortest’ path between two points is almost guaranteed to not be a straight line. Which makes using this measurement a basis for location… challenging…

Interesting sidenote; original matlab (not written by me) implementation was 8 seconds for each single execution stand alone. This however is calculated (for an 8 hour mission) around about 350,000 times for one simulation run, so after massaging with python and a few other tools, managed to bring down the single execution time to around half a second, which along with some memoisation techniques and other magicks leaves a total execution time of around 5-8 minutes.

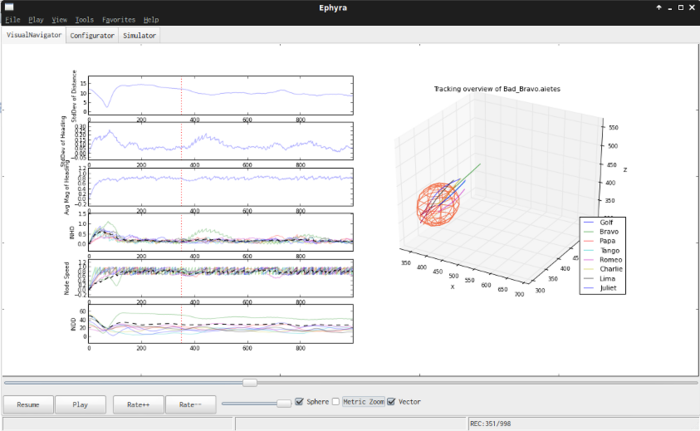

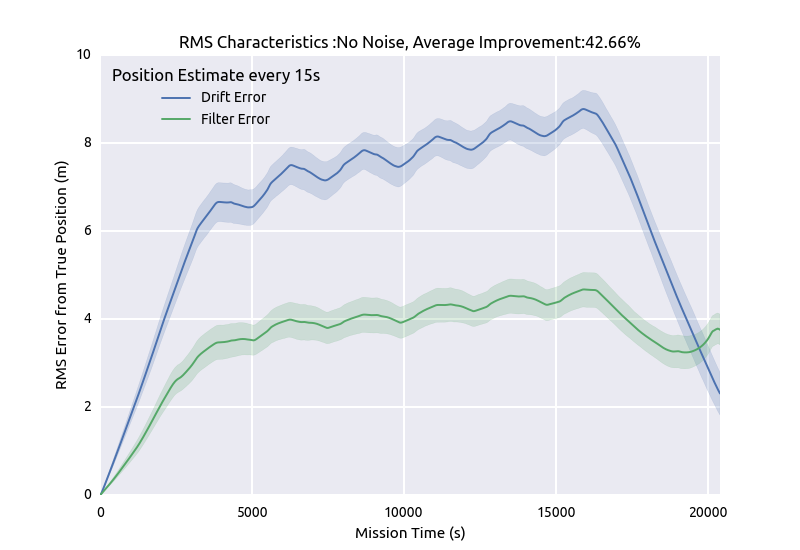

Still, since we’re dealing with normally distributed effects, we need a statistical sample…. meaning that my simulation runs currently take around 19 hours depending on what range of variables are under test at the time. They end up making pretty graphs like this.

Fin

So yeah, that’s what I do when I’m not Farsetting, just in case anyone forget I had an actual job! :D

-

Buchegger, S., & Le Boudec, J.-Y. (2002). Performance analysis of the CONFIDANT protocol. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM international symposium on Mobile ad hoc networking & computing - MobiHoc ’02 (p. 226). ACM Press. doi:10.1145/513800.513828 ↩

-

Li, R., Li, J., Liu, P., & Chen, H.-H. (2007). An Objective Trust Management Framework for Mobile Ad Hoc Networks. Vehicular Technology Conference,, 56–60. doi:10.1109/VETECS.2007.24 ↩

-

Guo, J., Marshall, A., & Zhou, B. (2011). A New Trust Management Framework for Detecting Malicious and Selfish Behaviour for Mobile Ad Hoc Networks. 2011IEEE 10th International Conference on Trust Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications, 142–149. doi:10.1109/TrustCom.2011.21 ↩

-

Zuo, F. (1995). Determining Method for Grey Relational Distinguished Coefficient. SIGICE Bull., 20(3), 22–28. doi:10.1145/202081.202086 ↩